Fingerprinting Soil Water Evaporation with Triple Oxygen Isotopes of Pedogenic Carbonates

Julia Kelson, Tyler Huth, Naomi Levin, and Ben Passey

Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor MI

Session 14d: Geochemical indicators of paste climate and environmental change Chat @ Monday June 22, 20:06-20:09 (EDT)

Intro | Triple Oxygen Isotope Results | Bonus modeling | Implications for Paleo & Future work | Detailed Methods

Introduction

Motivation: Soil (pedogenic) carbonates are an important archive of terrestrial paleoclimate. In particular, their oxygen isotope composition ($\delta$18O) is used to reconstruct the $\delta$18O of ancient meteoric waters.

The problem: To what extent is the $\delta$18O of soil water (and resulting soil carbonate) modified by evaporation? If soil carbonates form during evaporative dewatering, it is likely that their parent water $\delta$18O is modified by evaporation. If unrecognized, this could lead to erroneously high estimates of $\delta$18O of ancient precipitation. On the other hand, if soil carbonates form as a result of rootwater uptake and/or respiration-induced changes in soil CO2, the parent water $\delta$18O might be a faithful recorder of $\delta$18O of meteoric waters.

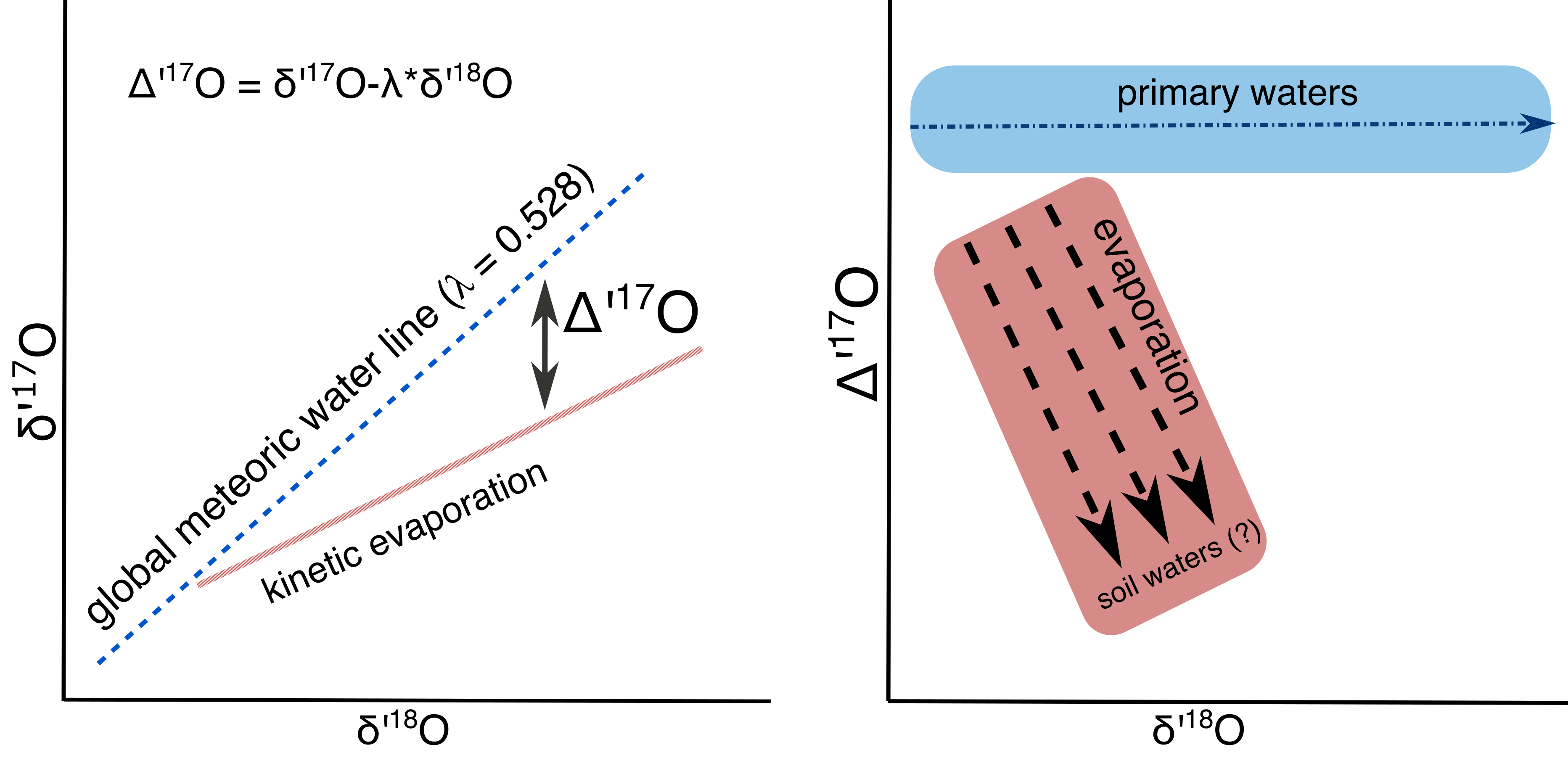

What we are doing: We are measuring the triple oxygen isotope composition of modern soil carbonates from various environments. Evaporation will cause a deviation from the expected relationship between $\delta$17O and $\delta$18O in water and resulting carbonate (Figure 1) (Landais et al., 2006; Luz and Barkan, 2010; Passey et al., 2014; Gázquez et al., 2018; Surma et al., 2018; Passey and Levin, in review). Thus the ∆’17O composition of soil carbonates should indicate the extent to which their parent soil waters were evaporated (Primer on Triple Oxygen Isotopes here).

Figure 1: Schematic of relationship between $\delta$’18O and $\delta$’17O (left panel) and $\delta$’18O and ∆’17O (right panel). ∆’17O is insensitive to the $\delta$’18O of the carbonate parent water. Evaporated waters will have low ∆’17O values relative to their parent waters.

Triple Oxygen Isotope Results

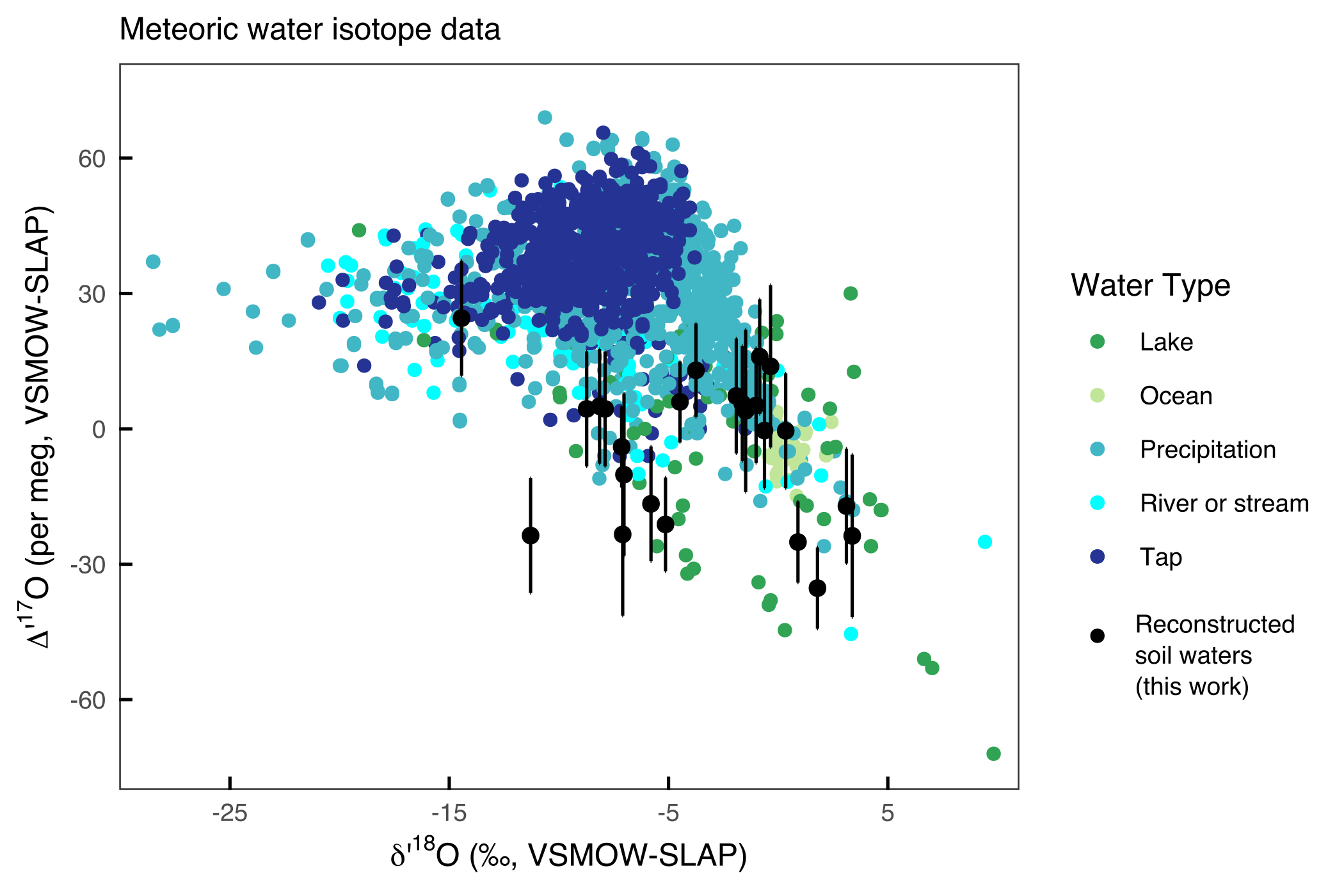

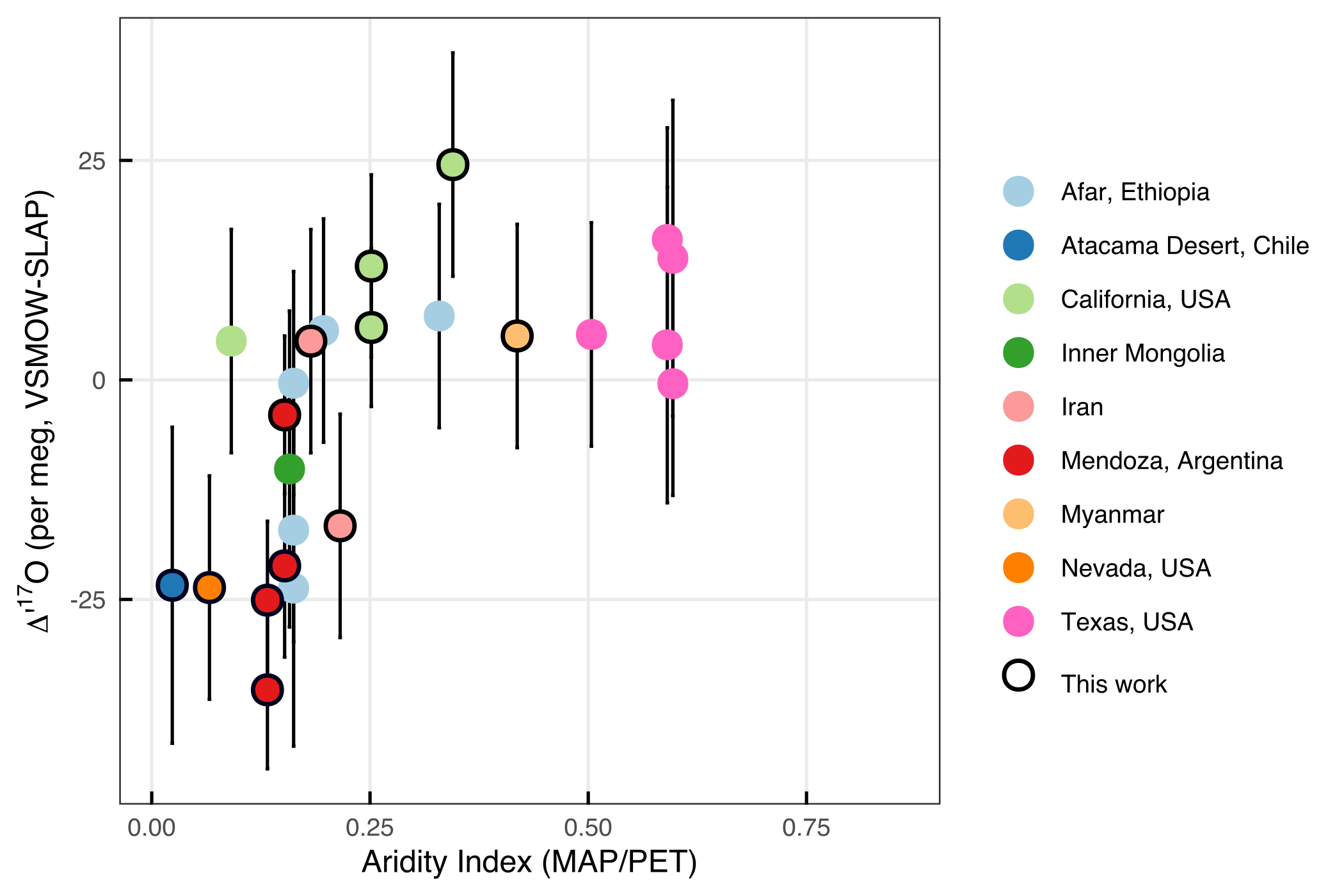

Preliminary results: Soil carbonate ∆’17O ranges from approximately -170 to -110 per meg, which corresponds with parent waters that range from -35 to + 25 per meg (Methods below) (Figure 2). These values are generally lower than unevaporated meteoric waters (i.e., rain and rivers), and at the lowest, resemble evaporated meteoric waters (i.e., closed basin lakes). Thus far, a complicated relationship between aridity and ∆’17O of soil carbonates is emerging. We speculate that there might be the hint of some kind of “threshold aridity.” Below such a threshold aridity (more arid) we observe a spread in ∆’17O. Above such a threshold (less arid) we observe relatively high ∆’17O values of soil waters (less evaporation). This pattern might indicate that soil carbonates form during evaporation in the most arid environments (aridity index, AI, < 0.2). In semi-arid to humid environments (AI > 0.2), soil carbonate forms via other processes and/or soil waters are regularly recharged with non-evaporated waters. In such an environment, $\delta$18O of soil carbonates might be more reliable recorders of rainfall $\delta$18O.

Figure 2: Reconstructed soil water ∆’17O (black dots) and ∆’17O of meteoric waters (Aron et al., Chem Geo, in prep) (colored dots). Reconstructed soil water ∆’17O values are low compared to most meteoric waters; we interpret this pattern as indicating that many soil waters overprinted by some amount of evaporation.

Figure 3: Calculated ∆’17O of soil waters reconstructed from soil carbonates. Aridity index (AI) is calculated as the mean annual precipitation (MAP) divided by potential evapotranspiration (PET) using WorldClim data (Beverly et al., 2019; Fick and Hijmans 2017). The black outline indicates data that is newly presented in this work (measurements made at the University of Michigan). The data from Texas, USA are from Ji (2016); all other data are from Passey et al. (2014).

Bonus: Modeling of Triple Oxygen Isotopes in a Soil Profile

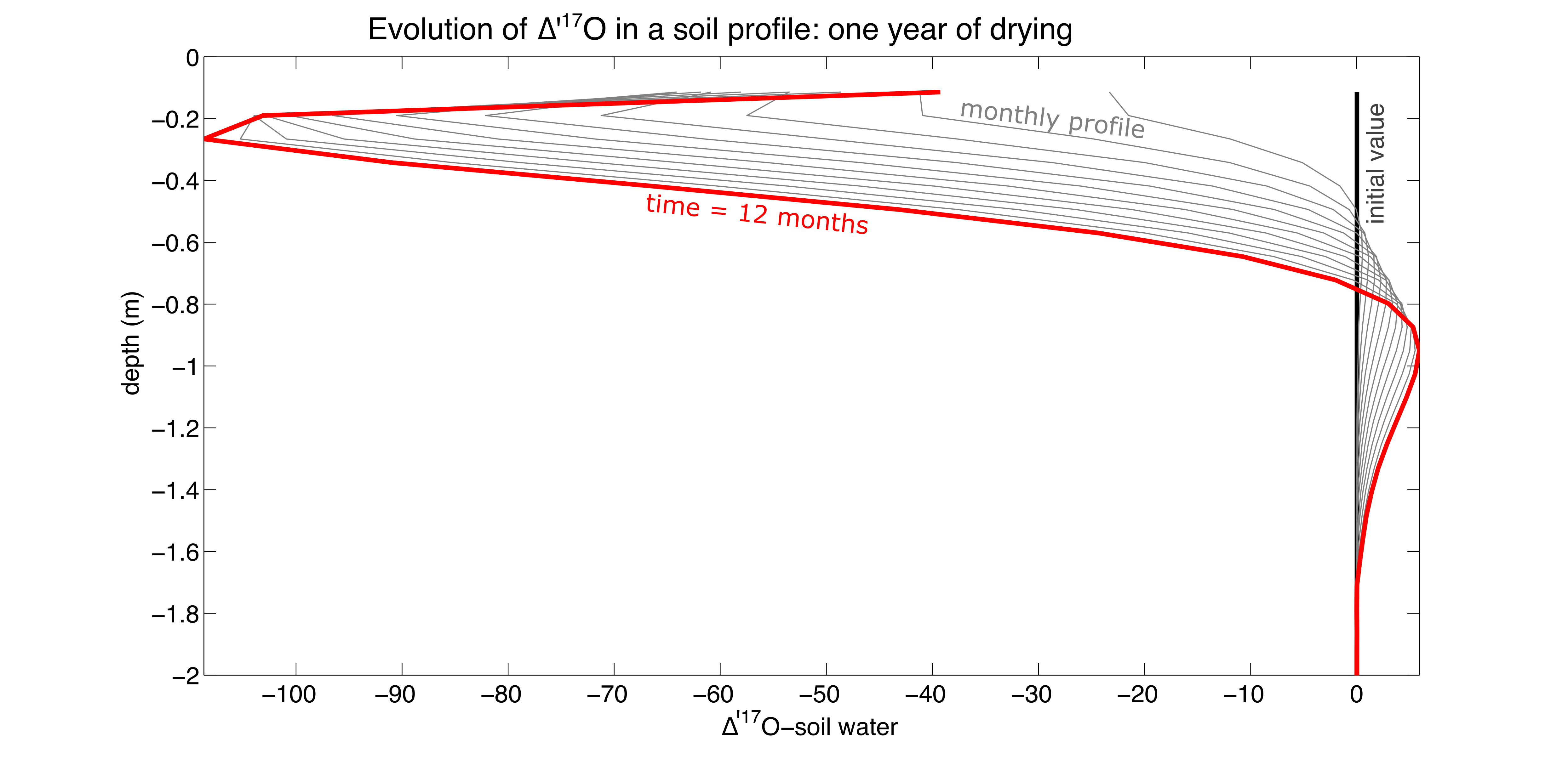

Evaporation only: We’ve started to model ∆’17O in a soil profile using the TOUGHREACT numerical simulation program. Below, we have plotted monthly time steps for a 1-D soil profile undergoing one year of evaporation (Figure 4). The model is isothermal, atmospheric relative humidity is set to 40 %, and the model does not incorporate transpiration. The year of evaporation results in an enormous ∆’17O-soil water excursion – up to -100 per meg lower than starting ∆’17O (0 per meg) [see also the similar theoretical profile of Barnes and Allison (1983)]. Because a year of uninterrupted evaporation would only occur in the driest locations on earth (e.g., the non-vegetated Atacama Desert), this scenario shows the maximum potential effect of evaporation on ∆’17O-soil water and therefore ∆’17O-soil carbonate.

Figure 4: Modeling D’17O of a soil profile. One year of evaporation (isothermal soil profile).

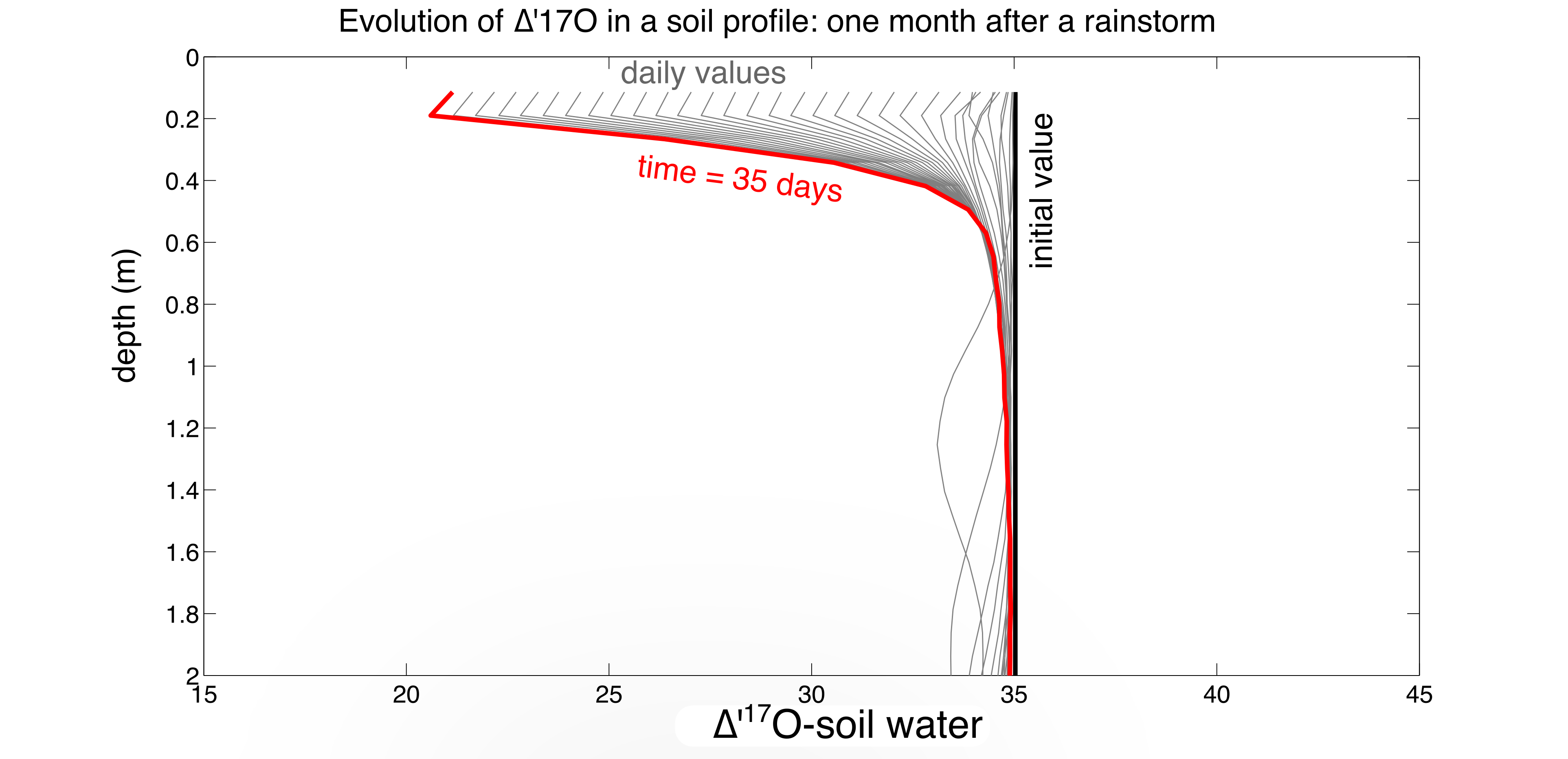

A little more realistic: To give a sense of the range of ∆’17O-soil water in a more realistic scenario, we modeled the Adams Ranch Soil Climate Analysis Network site in central New Mexico, a semi-arid environment (mean annual precipitation of 230 mm/yr) where soil carbonate readily forms. As above, we modeled an isothermal, non-vegetated system (soil temperature = 15 °C, atmospheric relative humidity = 44 %). Figure 5 below shows the evolution of soil water ∆’17O after the largest rain event on record (initial value of +35 per meg) from 2011–2015, ending just before the next rain event (Figure 5). The results suggest that ∆’17O excursions of up to 20-25 per meg are possible from evaporation alone, although after most rain events ∆’17O-soil water only changes by 10-15 per meg before the next infiltration event.

Figure 5: Time steps of ∆’17O-soil water after the September 10, 2013 rain event at Adam’s Ranch, New Mexico. The ∆’17O of soil water resets to the rainfall value (+35 per meg) after a storm, then evolves to lower ∆’17O with drying; the plot stops at 35 days, just before the next rain event. Soil profile is held at 15 °C, atmosphere at 12.5 °C.

Conclusions

Implications for paleoclimate reconstructions:

- ∆’17O of soil carbonates can identify if parent soil waters have been evaporated. This will help workers evaluate the fidelity of their record for reconstructing $\delta$18O of meteoric waters.

- ∆’17O promises to shed light on soil carbonate formation processes, with implications on how to interpret other stable isotope data from this widely used material.

- Preliminary data suggests that ∆’17O of soil carbonates relates to local aridity. More data will be required to establish this measurement as a true proxy for aridity.

Future work:

- Firstly, we need to finish the replicate analyses that were aborted when the University of Michigan shut down to slow the spread of Sars-Cov-2.

- We’re also interested in adding to our soil carbonate collection.

- We plan to explore other environmental factors (i.e., external constraints on timing of carbonate formation, seasonality of precipitation, vegetation type, etc.) that might also explain the ∆’17O variation that we observe.

- Observations of local meteoric water ∆’17O would give context to our reconstructed soil water values.

- We are just starting numerical modeling of ∆’17O of soil waters (link to bonus figures below)

- Future, future work: measurements of ∆’17O of soil water made through a seasonal cycle would be very useful.

Do you have samples to contribute? We are still expanding our collection of soil carbonate samples to include in this study. We are most interested in soil carbonate samples that already have some kind of environmental or isotope context (i.e., stable and/or clumped isotope data, water isotope data, vegetation information, etc.). If you have samples from anywhere in the world that you’d like to share with us, please get in touch!

Acknowledgements This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Award No. 1854873 to JRK. We’d like to thank Greg Hoke, Alexis Licht and Paolo Ballato for providing soil carbonate samples from Argentina, Myanmar, and Iran. Drake Yarian provided analytical assistance, usually with a good sound track. TOUGHREACT and Tyler Huth’s training was funded through NSF grant EAR 1325214 to Thure Cerling and Diego Fernandez at the University of Utah.

Stable isotope methods:

Triple oxygen isotope measurements are being made at the IsoPaleoLab at the University of Michigan. We are using the acid digestion/reduction/fluorination method described in Passey et al. (2014). Multiple analyses of VSMOW2 and SLAP2 are performed during each analytical session and form the basis for normalization to the VSMOW-SLAP reference frame (Schoenemann et al., 2013). International carbonate standards (NBS-18, NBS-19, IAEA 603) are analyzed along with unknowns, and an internal carbonate standard (102-GC-AZ01) is used to correct for systematic drift in ∆’17O that is observed in some analytical sessions. The data shown in this presentation were analyzed in two analytical sessions (as established by CoF3 reactors number 13 and 14 at IPL). These sessions spanned from December 2019 to March 2020.

Where shown, ∆’17O of soil waters is reconstructed from the soil carbonates using the ∆’17O of soil carbonate, an estimate of growth temperature from clumped isotopes (∆47) and a combined mineral-water and acid fractionation factor of $\theta$a-c-w = 0.5242 (Passey et al., 2014). The 18$\alpha$a-c-w is calculated using the equation from Kim and O’Neil (1997) and multiplied by an acid fractionation factor of 1.0081 for acid digestion of calcite at 90 °C (Kim et al., 2007):

18⁄16$\alpha$a-c-w = 1.0081*$e^{((18030/(T)-32.42)/1000)}$

$\theta$a-c-w = ln(17⁄16 $\alpha$a-c-w)/ln(18⁄16 $\alpha$a-c-w)

where T is carbonate growth temperature in Kelvin.

Error bars in ∆’17O are 1 standard error, which is calculated by dividing the standard deviation of 0.018 (long-term SD of an internal carbonate standard, 102-GC-AZ01) by the square root of the number of replicate analyses.

References

Aron, P.G., Levin, N.E., Beverly, E.J., Huth, T.E., Passey, B.H., Pelletier, E.M., Poulsen, C.J., Winkelstern, I.Z., Yarian, D.A. (in prep). Global variations of triple oxygen isotopes in meteoric waters. Chemical Geology, to be submitted by June 30, 2020.

Barnes C. J., and Allison G. B. (1983). The distribution of Deuterium and 18O in dry soils: 1. Theory. Journal of Hydrology, 60, 141–156. Fick, S. E., and Hijmans, R. J. (2017). WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. of Climatol. 37, 4302–4315.

Beverly, E.J., Levin, N.E., Passey, B.H., Aron, P., and Page, M., 2019, Using triple oxygen and clumped isotopes in soils to understand the hydrosphere in Critical Zones, GSA Abstracts with Programs, v. 51, no. 5.

Gázquez, F., Evans, N. P., Herwartz, D., Bauska, T. K., Morellon, M., Surma, J., … & Hodell, D. A. (2016, December). Triple Oxygen and Deuterium Isotopes in Gypsum Hydration Water for Quantitative Paleo-humidity Reconstructions. In AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts.

Ji, H. (2016). Triple oxygen isotopes in lake waters, lacustrine carbonates and soil carbonates: An indicator for evaporation (Doctoral dissertation, Johns Hopkins University).

Kim, S. T., & O’Neil, J. R. (1997). Equilibrium and nonequilibrium oxygen isotope effects in synthetic carbonates. Geochimica et cosmochimica acta, 61(16), 3461-3475.

Kim, S. T., Mucci, A., & Taylor, B. E. (2007). Phosphoric acid fractionation factors for calcite and aragonite between 25 and 75 C: revisited. Chemical Geology, 246(3-4), 135-146.

Landais, A., Barkan, E., Yakir, D., & Luz, B. (2006). The triple isotopic composition of oxygen in leaf water. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 70(16), 4105-4115.

Luz, B., & Barkan, E. (2010). Variations of 17O/16O and 18O/16O in meteoric waters. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 74(22), 6276-6286.

Passey, B. H., Hu, H., Ji, H., Montanari, S., Li, S., Henkes, G. A., & Levin, N. E. (2014). Triple oxygen isotopes in biogenic and sedimentary carbonates. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 141, 1-25.

Passey, B.H. and Levin, N.E. (in review) Triple oxygen isotgopes in carbonates, biological apatites, and continental paleoclimate reconstruction. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry.

Schoenemann, S. W., Schauer, A. J., & Steig, E. J. (2013). Measurement of SLAP2 and GISP δ17O and proposed VSMOW‐SLAP normalization for δ17O and 17Oexcess. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 27(5), 582-590.