A dummie’s guide to triple oxygen isotopes in carbonate.

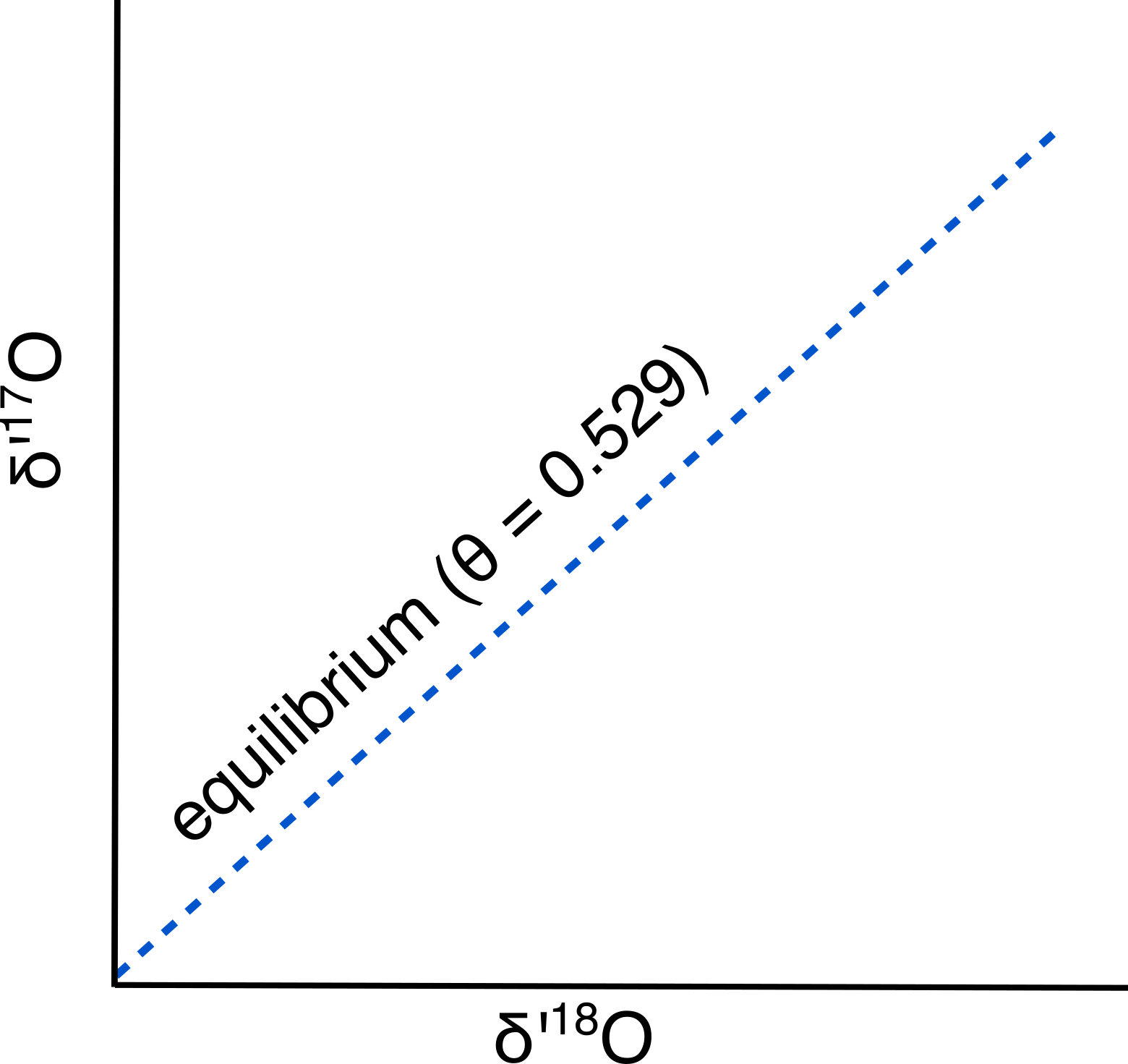

Oxygen has one major isotope, 16O, and two minor isotopes, 17O and 18O. A measurement of the abundance of 18O is widely used in geochemistry ($\delta$18O) as a tracer for hydrologic processes. It was long assumed that stuyding 17O would not yield additional useful information because the fractionation would be about half that of 18O, following a relationship that is predicted by mass-dependent (equilibrium) fractionation ($\theta$ = 0.529 for equilibrium fractionation, Luz and Barkan 2010):

Figure 1: Predicted relationship between $\delta$’18O and $\delta$’17O given equilibrium fractionation. $\theta$a-b = ln(17⁄16 $\alpha$a-b)/ln(18⁄16 $\alpha$a-b), where $\alpha$a-b is the fractionation factor between two phases (like calcite-water).

Note that the axes of Figure 1 use “delta-prime” notation, a slight variation on the more familiar delta notation. This notation is used to remove the slight curvature in the relationship between $\delta$18O and $\delta$17O (Miller, 2002):

$\delta$’x = ln($\delta$x+1)

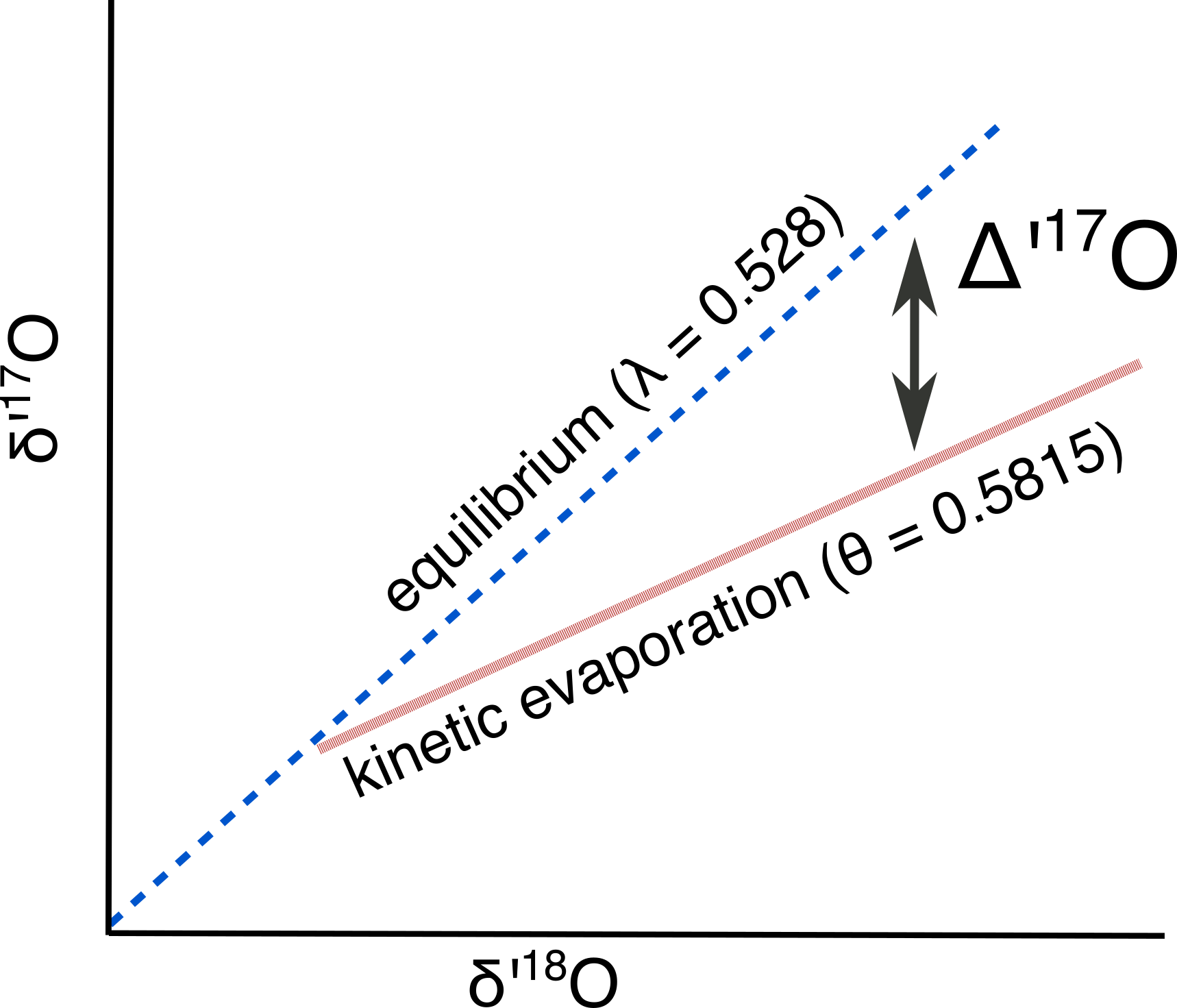

$\delta$17O can deviate from this relationship if non-equilibrium fractionation occurs (i.e., $\theta$ ≠ 0.529). Evaporation is an example of one such fractionation process that carries $\theta$ = 0.5185 (Barkan and Luz, 2007). Yes, 0.5185 might seem about the same as .529, but with sufficiently high precision instruments this deviation can be measured. This deviation from the expected relationship between $\delta$’17O and $\delta$’18O is called ∆’17O, (analogous to the familiar d-excess), and is defined as:

$\Delta$’17O = $\delta$’17O – $\lambda$ * $\delta$’18O

Figure 2: Schematic of $\Delta$’17O

Note that I’ve used $\lambda$ = 0.528, which is the empirically observed relationship in meteoric waters (Luz and Barkan 2010). The $\lambda$ notation expresses that it is an empirical relationship that may combine a number of different fractionations, as opposed to the $\theta$ used above that describes a single, well-defined fractionation (like the equilibrium fractionation, diffusion, or acid fractionation). ∆’17O is expressed in permille (with values that ranges from +0.10 to -0.2), or in per meg (with values that range from +100 to -200).

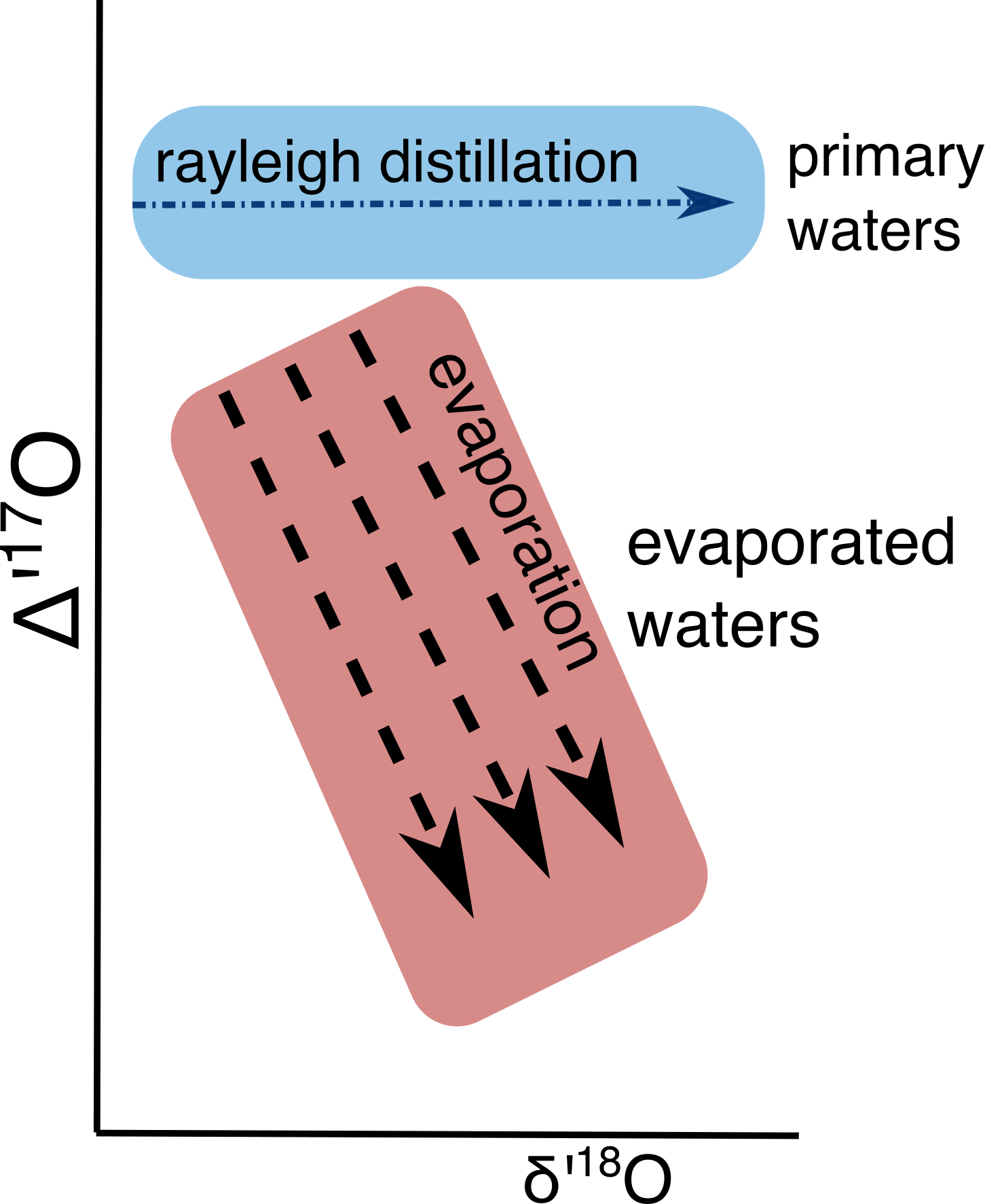

Thus, $\Delta$’17O can be used to identify evaporation of parent waters and carbonate minerals. Measuring $\Delta$’17O promises to be useful in terrestrial hydroclimate where d18O alone can be ambiguous. Let’s consider the water bottle of Seattle tap water ($\delta$18O = -10 ‰) that I accidentally brought with me when I moved to in Michigan last fall. If I let this water bottle sit with a lid off, it would evaporate and eventually reach a $\delta$18O= -6 ‰. At that point, it would be impossible to distinguish my imported Seattle water from that of local Ann Arbor tap water using $\delta$18O analyses. $\Delta$’17O could be used to readily identify which water was evaporated; the Seattle water would have a $\Delta$’17O value that is about 0.10 ‰ lower than that of the Michigan water (evaporation experiments in Li et al., 2017).

$\Delta$’17O has the potential to be useful in addition to the more familiar d-excess for two reasons. The first is the fractionation in oxygen isotopes is not very sensitive to temperature (i.e., Angert et al., 2004). The second is that carbonate minerals are widely preserved in the geologic record, where it is difficult to find co-occurring preservation of hydrogen and oxygen that would be necessary to calculate d-excess. Furthermore, the growth temperature can be directly measured from the same carbonate mineral (using clumps), allowing for a simultaneous estimate of environmental temperature and hydrologic processes.

Figure 3: Schematic of $\Delta$’17O vs $\delta$’18O in waters

In studies of paleo-hydroclimate, we could use ∆’17O to parse out if changes in $\delta$18O were due to Rayleigh distillation (i.e., rainout over a mountain range) or due to evaporation. Other processes that cause kinetic fractionation could also be investigated (i.e., speleothems, as predicted in Guo and Zhou, 2019). Note that ∆’17O should be independent of the starting $\delta$18O composition. It might even be possible to use the ∆’17O of carbonates to reconstruct the $\delta$18O of primary meteoric waters (i.e., lake carbonates in Passey and Ji, 2019).

Measuring ∆’17O in carbonate materials posed a technical challenge to isotope geochemists. Usually the isotopic composition of a carbonate mineral is determined by first digesting the CaCO3 in phosphoric acid, then measuring the isotope abundances in the evolved CO2 gas. However, 13C-16O-16O interferes with the measurement of 12C-17O-16O. So, CO2 gas evolved from solid CaCO3 needs to be converted to O2 for measurement. Passey et al. (2014) describe the acid digestion, reduction, and fluorination method which is currently in place at the University of Michigan.