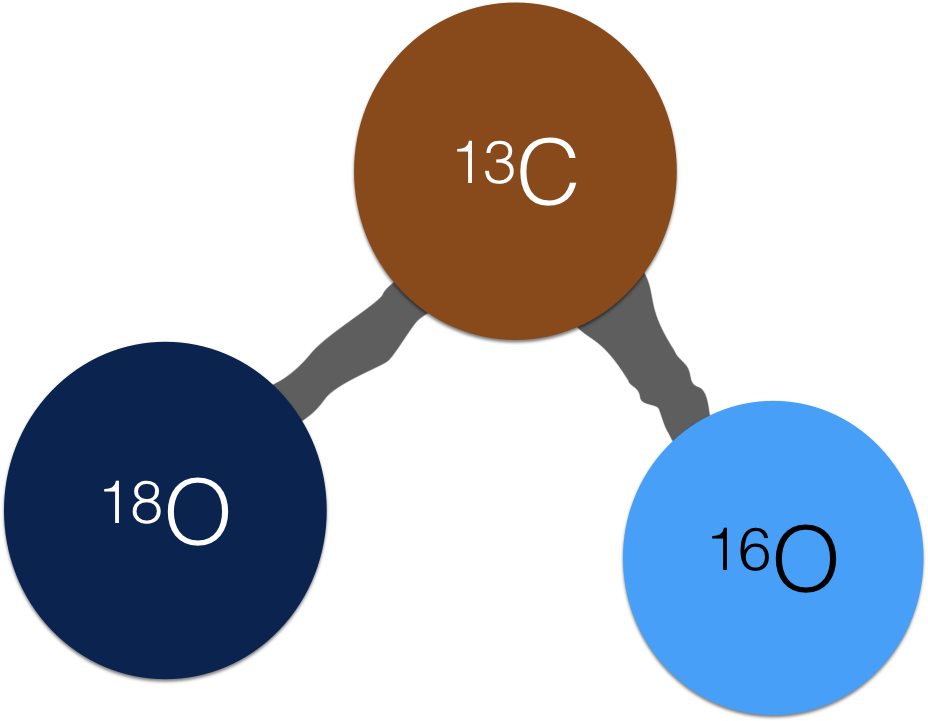

a clumpy CO2 molecule

The term ‘clumped isotopes’ refers to the co-existence of two rare, heavy isotopes in a single molecule, or - get ready for a mouthful – a ‘doubly substituted isotopologue’. In the CO2 molecule above, there are heavy isotopes (18O and 13C) bonded together. (FYI, their common/light counterparts are 12C and 16O). This makes for a molecule with an atomic mass of 47, hence the common ∆47 notation for ‘clumped isotopes’. Conveniently for paleoclimatologist, the rare/heavy isotopes preferentially clump at lower temperatures.

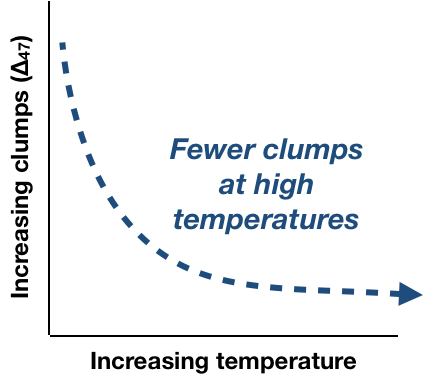

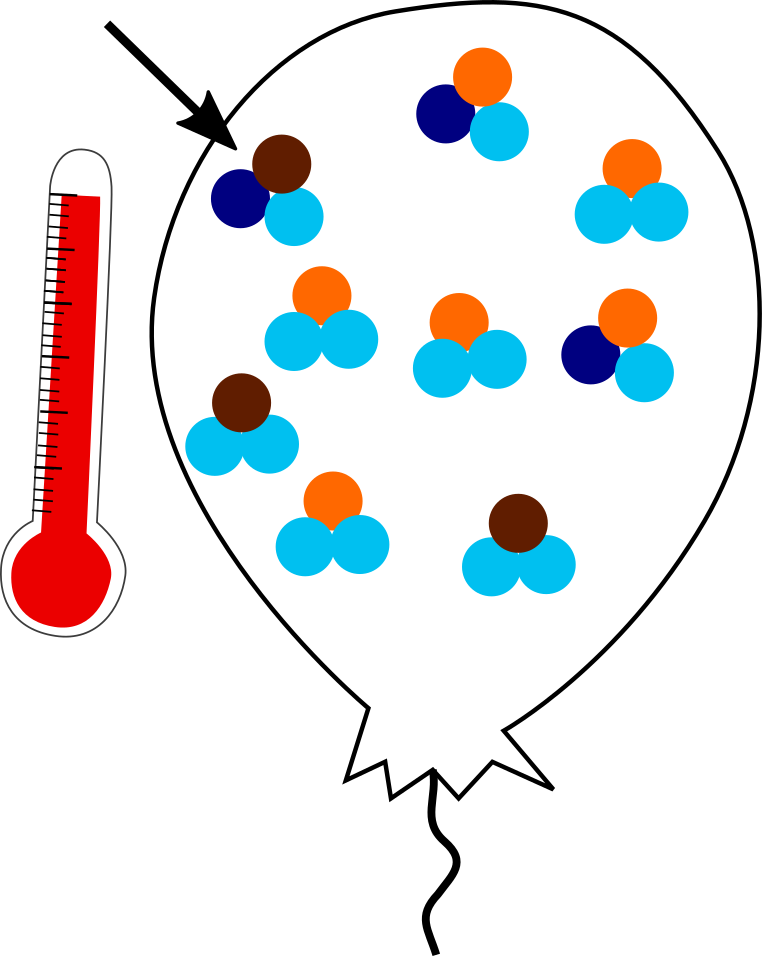

But how does this work? Let’s imagine a balloon full of CO2 gas with a fixed number of light and heavy isotopes each. In a balloon held at 1000 °C, the system is chaotic. Bonds are vibrating and wiggling and nothing really settles down. In this high-temperature system, the heavy and light isotopes end up being randomly distributed amongst the molecules.

Only one clumpy molecule in the hot balloon. Heavy isotopes are dark colors, light isotopes are light colors.

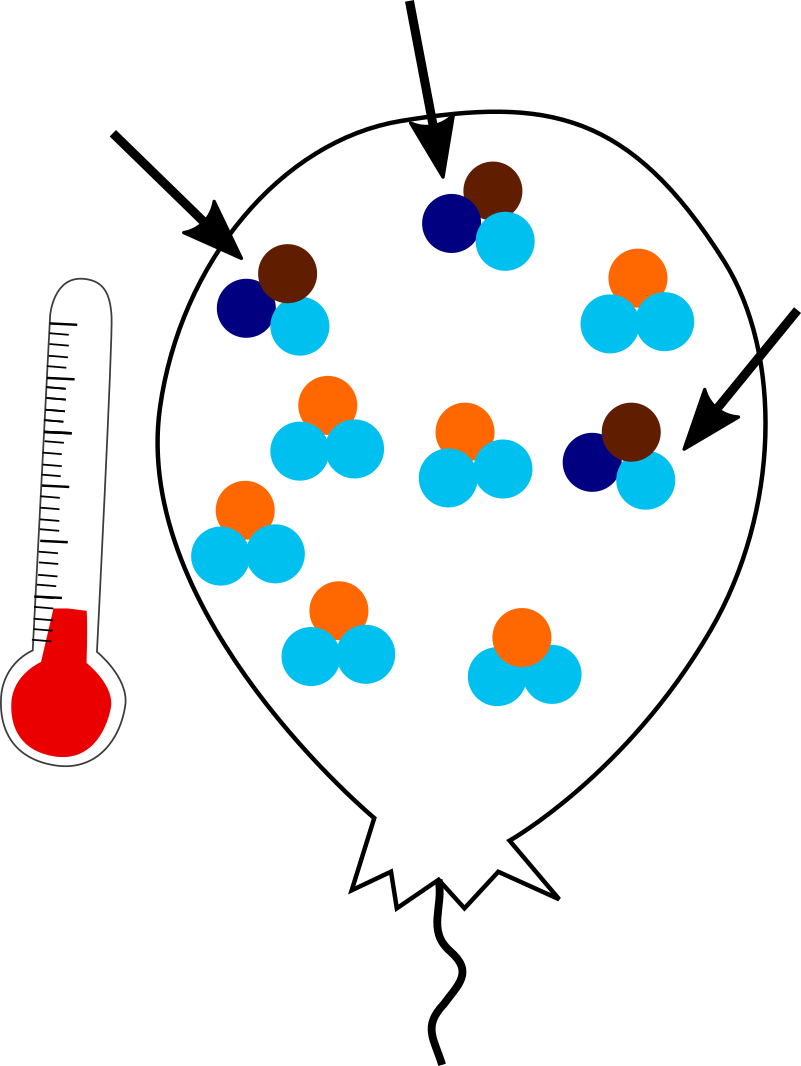

In a balloon held at lower temperatures (<1000 °C), the system can reach a more energetically favorable state. Clumping heavy isotopes together is favorable because it slightly reduces the vibrational energy and increases bond strength. So more clumps will occur at lower temperatures.

Three clumpy molecules in the cold balloon. Note same number of heavy isotopes.

Thus, clumped isotope geochemistry is not concerned with the total number of heavy isotopes in a system, but rather how those heavy isotopes are arranged within the molecules. We do need to know the number of heavy isotopes in the system, though, so we can calculate how many clumps we would expect if they were randomly arranged vs. how many we actually have measured. Then, we can estimate the temperature at which that CO2 molecule formed!

Usually, what is measured is the clumpiness of CO2 gas that we get by digesting a carbonate mineral in acid. Common targets are soil carbonates and shells. With a little bit more work (see other projects), we can use the clumpiness we measure to estimate temperatures at or near the surface of the Earth millions of years ago. This thermometer is not based on biology nor does it depend on the isotopic composition of the water from which the mineral grew. That makes for a powerful, quantitative thermometer.